11 books in which famous scientists from different fields of science share their experiences, observations and theories in a way that is understandable, interesting and useful for everyone.

Stephen Fry. "The Book of General Delusions"

Stephen Fry on his "Book of General Fallacies": "If you liken all the knowledge accumulated by mankind to sand, then even the most brilliant intellectual will be like a person to whom one or two grains of sand accidentally stuck."

Annotation. The Book of Common Delusions is a collection of 230 questions and answers. Stephen Fry helps the reader get rid of often encountered pseudoscientific prejudices, myths, false facts through a chain of reasoning and real evidence. The reader will find in the book answers to completely different questions: what color is Mars really, where is the driest place on Earth, who invented penicillin and more. It's all written in typical Stephen Fry style - witty and engaging. Critic Jennifer Kay argues that The Book of Common Misconceptions will not make us feel stupid, but will make us more curious.

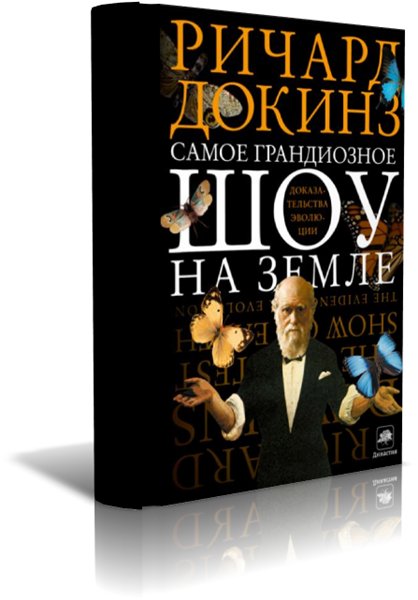

Richard Dawkins. "The Greatest Show on Earth: Evidence for Evolution"

Comments by Neil Shubin, associate of Richard Dawkins and bestselling author of The Inner Fish: “To call this book an apology for evolution would be to miss the point. "Most grand show on Earth” is a celebration of one of the most significant ideas… Reading Dawkins, one is in awe of the beauty of this theory and bows to the ability of science to answer some of life’s greatest mysteries.”

Annotation. The world famous biologist Richard Dawkins considers evolution to be the only possible theory of the origin of all living things and supports his point of view with evidence. The Greatest Show on Earth: Evidence for Evolution explains how nature works and how certain animal species, including humans, appeared on Earth. After reading his book, even an adherent of the divine theory will not find arguments against evolution. Dawkins' bestseller came out on the 200th anniversary of Darwin and the 150th anniversary of his On the Origin of Species.

Stephen Hawking. "A Brief History of Time"

Stephen Hawking on his book A Brief History of Time: “All my life I have marveled at the major questions we face and tried to find a scientific answer to them. Maybe that's why I've sold more books on physics than Madonna has on sex."

Annotation. In his youth, Stephen Hawking was forever paralyzed by atrophic sclerosis, only the fingers of his right hand remained mobile, with which he controls his chair and voice computer. In 40 years of activity, Stephen Hawking has done as much for science as a whole generation of healthy scientists has not done. In the book A Brief History of Time, the famous English physicist tries to find answers to eternal questions about the origin of our universe. Each person at least once thought about how the Universe began, whether it is immortal, whether it is infinite, why there is a person in it and what the future holds for us. The author took into account that the general reader needs fewer formulas and more clarity. The book was published back in 1988 and, like any work by Hawking, was ahead of its time, so it is a bestseller to this day.

David Bodanis. "E=mc2. Biography of the most famous equation in the world

Annotation. David Bodanis teaches at European universities, writes brilliant popular science books and popularizes technical sciences in every possible way. Inspired by Albert Einstein's revolutionary discovery in 1905, the equation E=mc2, David Bodanis opened up new ways to understand the universe. He decided to write simple book about the complex, likening it to an exciting detective story. The heroes in it are outstanding physicists and thinkers such as Faraday, Rutherford, Heisenberg, Einstein.

David Matsumoto. “Man, culture, psychology. Amazing mysteries, research and discoveries»

David Matsumoto on the book: "When cultural differences emerge in the study of culture and psychology, natural questions arise about how they arose and what makes people so different."

Annotation. Professor of Psychology and Ph.D. David Matsumoto has made many contributions both to the practice of psychology and intercultural relations and to the world of martial arts. In all his works, Matsumoto refers to the diversity of human connections, and in the new book he is looking for answers to strange questions, for example, about the incompatibility of Americans and Arabs, about the relationship between GDP and emotionality, about people's everyday thoughts ... Despite the easy presentation, the book is scientific labor, and not a collection of conjectures. “Man, culture, psychology. Amazing mysteries, research and discoveries treatise but rather an adventure novel. Both scientists and ordinary readers will find food for thought in it.

Frans de Waal. "The origins of morality. In search of the human in primates"

Frans de Waal on his "Origins of Morality": "Morality is not a purely human property, and its origins must be sought in animals. Empathy and other manifestations of a kind of morality are inherent in monkeys, and dogs, and elephants, and even reptiles.

Annotation. For many years, the world-renowned biologist Frans de Waal has studied the lives of chimpanzees and bonobos. After researching the animal world, the scientist was struck by the idea that morality is inherent not only in humans. The scientist studied the life of great apes for many years and found real emotions in them, such as grief, joy and sadness, then he found the same in other animal species. Frans de Waal touched upon issues of morality, philosophy, and religion in the book.

Armand Marie Leroy. "Mutants"

Armand Marie Leroy on "Mutants": "This book is about how the human body is created. About techniques that allow a single cell, immersed in the dark nooks and crannies of the womb, to become an embryo, fetus, child, and finally an adult. It provides an answer, albeit tentative and incomplete, yet clear at its core, to the question of how we become what we are.”

Annotation. Armand Marie Leroy traveled with early childhood, became a renowned evolutionary biologist, Ph.D., and teacher. In Mutants, biologist Armand Marie Leroy explores the body through the shocking stories of mutants. Siamese twins, hermaphrodites, fused limbs... Once Cleopatra, being interested in human anatomy, ordered pregnant slaves to rip open their stomachs... Now such barbaric methods are in the past and science is developing with the help of humane research. Formation human body still not fully understood, and Armand Marie Leroy shows how the human anatomy remains stable despite genetic diversity.

John Lehrer. "How We Make Decisions"

Foreword by Jonah Lehrer to her book: "Each of us is capable of coming to a successful decision."

Annotation. The world-famous popularizer of science, John Lehrer, has gained a reputation as a connoisseur of psychology and a talented journalist. He is interested in neuroscience and psychology. In her book How We Make Decisions, Jonah Lehrer describes the mechanics of decision making. He explains in detail why a person chooses what he chooses, when to indulge intuition, how to do right choice. The book helps to better understand yourself and the choices of other people.

Frith Chris. “Brain and soul. How nervous activity shapes our inner world

Frith Chris on the book "Brain and Soul": "We need to look a little more at the connection between our psyche and the brain. This connection must be close ... This connection between the brain and the psyche is imperfect.

Annotation. The famous English neuroscientist and neuropsychologist Frith Chris studies the device human brain. On this topic, he wrote 400 publications. In the book "Brain and Soul" he talks about where images and ideas about the world come from in the head, as well as how real these images are. If a person thinks that he sees the world as it is in reality, then he is greatly mistaken. The inner world, according to Frith, is almost richer than the outer world, since our mind itself conjectures the past, present and future.

Michio Kaku. "Physics of the Impossible"

Quote by Michio Kaku from the book The Physics of the Impossible: “I have been told more than once that in real life you have to give up the impossible and be content with the real. For my short life I have often seen how what was previously considered impossible turns into an established scientific fact.

Annotation. Michio Kaku is Japanese by origin and American by citizenship, is one of the authors of string theory, a professor, and a popularizer of science and technology. Most of his books are international bestsellers. In the book "Physics of the Impossible" he talks about the incredible phenomena and laws of the universe. From this book, the reader will learn what will become possible in the near future: force fields, invisibility, mind reading, communication with extraterrestrial civilizations and space travel.

Stephen Levitt and Stephen Dubner. Freakonomics

“Stephen Levitt tends to see a lot of things very differently than any other average person. His point of view is not like the usual thoughts of the average economist. It can be great or terrible, depending on how you think about economists in general.” – New York Times Magazine

Annotation. The authors seriously analyze the economic background of everyday things. A non-standard explanation of such strange economic issues as quackery, prostitution and others. Shocking, unexpected, even provocative topics are considered through logical economic laws. Steven Levitt and Steven Dubner sought to awaken interest in life and deservedly received many flattering reviews. Freakonomics was written not by ordinary economists, but by real creatives. She was even included in the list best books decades according to the Russian Reporter.

10 most popular and interesting science books from a variety of fields human knowledge, of course, will not make you a scientist immediately after reading them. But they will help you better understand how a person works, our whole world, and the rest of the universe.

"Big, Small, and the Human Mind". Stephen Hawking, Roger Penrose, Abner Shimoni, Nancy Cartwright.

The book is based on the Tenner Lectures delivered in 1995 by the famous English astrophysicist Roger Penrose and the controversy they provoked with equally famous English scientists Abner Shimoni, Nancy Cartwright and Stephen Hawking. The range of problems discussed includes the paradoxes of quantum mechanics, issues of astrophysics, theory of knowledge, and artistic perception.

"Big Atlas of Anatomy". Johannes V. Roen, Chihiro Yokochi, Elke Lutyen - Drekoll.

This edition is a worldwide bestseller. The reader is offered: unique photos anatomical cuts, most accurately conveying color and structural features of the structure of organs; tutorials that complement and explain the gorgeous color photographs of anatomical sections; didactic material covering the functional aspects of the structure of organs and systems; the principle of studying sections "from external to internal", when parrying in the laboratory and in clinical work; introduction, devoted to the description of modern methods of visualization of structural features of organs and systems of the body. For the convenience of the professional reader, the names of organs and systems are given in Russian and Latin.

"A Brief History of Almost Everything". Bill Bryson.

This book is one of the major popular science bestsellers of our day, a classic of popular science. It contains the Big Bang and subatomic particles, primordial oceans and ancient continents, giant lizards roam under its cover and primitive hunters track down their prey ... But this book is not only about the distant past: it tells about the cutting edge of science in an accessible and exciting way, about the incredible discoveries made by scientists, about global threats and the future of our civilization.

"Hyperspace. Scientific odyssey through Parallel Worlds, holes in time and the tenth dimension". Michio Kaku.

Instinct tells us that our world is three-dimensional. Based on this idea, scientific hypotheses have been built for centuries. According to the eminent physicist Michio Kaku, this is the same prejudice as the belief of the ancient Egyptians that the Earth was flat. The book is devoted to the theory of hyperspace. The idea of multidimensionality of space caused skepticism, was ridiculed, but is now recognized by many authoritative scientists. The significance of this theory lies in the fact that it is able to unite all known physical phenomena into simple design and lead scientists to the so-called theory of everything. However, there is almost no serious and accessible literature for non-specialists. This gap is filled by Michio Kaku, explaining with scientific point vision and the origin of the Earth, and the existence of parallel universes, and time travel, and many other seemingly fantastic phenomena.

"Microcosm. E. coli and the new science of life. Carl Zimmer.

E. coli, or E. coli, is a microorganism that we encounter almost daily, but which is one of the most important tools of biological science. Many of the biggest events in the history of biology are associated with it, from the discovery of DNA to the latest achievements. genetic engineering. E. coli is the most studied living thing on Earth. Interestingly, E. coli is a social microbe. The author draws surprising and disturbing parallels between the life of E. coli and our own life. He shows how this microorganism is changing almost before the eyes of researchers, revealing to their astonished eyes the billions of years of evolution encoded in its genome.

"Earth. Illustrated Atlas. Michael Allaby.

A comprehensive picture of all processes occurring on the Earth, inside and around it. The publication contains: detailed maps of continents and oceans. Impressive colorful photos. Popularly stated complex concepts. Broad overview of environmental issues. An exciting story of life on Earth. Explanatory diagrams and drawings. Reconstruction of geological processes. Terminological dictionary and alphabetical index. The Atlas will become an indispensable reference tool and handbook for readers of all ages.

"History of the Earth. From stardust to a living planet. The first 4,500,000,000 years". Robert Hazen.

The book of the famous popularizer of science, Professor Robert Hazen, introduces us to a fundamentally new approach to the study of the Earth, in which the history of the origin and development of life on our planet and the history of the formation of minerals are intertwined. An excellent storyteller, Hazen from the first lines captivates the reader with a dynamic narrative about the joint and interdependent development of animate and inanimate nature. Together with the author, the reader takes a breathless journey through billions of years: the emergence of the Universe, the appearance of the first chemical elements, stars, solar system and finally, education and a detailed history of the Earth. The movement of entire continents through thousands of kilometers, the rise and fall of huge mountain ranges, the destruction of thousands of species of terrestrial life and full change landscapes under the influence of meteorites and volcanic eruptions - the reality turns out to be much more interesting than any myth.

"The evolution of man. In 2 books. Alexander Markov.

The new book by Alexander Markov is a fascinating story about the origin and structure of man, based on the latest research in anthropology, genetics and evolutionary psychology. The two-volume book "The Evolution of Man" answers many questions that have long interested Homo sapiens. What does it mean to be human? When and why did we become human? In what are we superior to our neighbors on the planet, and in what are we inferior to them? And how can we better use our main difference and dignity - a huge, complex brain? One way is to read this book thoughtfully. Alexander Markov - Doctor of Biological Sciences, Leading Researcher at the Paleontological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences. His book on the evolution of living beings, The Birth of Complexity (2010), has become an event in non-fiction literature and has been widely acclaimed by readers.

"The Selfish Gene". Richard Dawkins.

We are created by our genes. We animals exist to preserve them and serve only as machines to ensure their survival. The world of the selfish gene is a world of fierce competition, ruthless exploitation and deceit. But what about acts of altruism seen in nature: bees committing suicide when they sting an enemy to protect a hive, or birds risking their lives to warn a flock of a hawk's approach? Does this contradict fundamental law about the selfishness of the gene? In no case! Dawkins shows that the selfish gene is also the cunning gene. And he cherishes the hope that kind of Homo sapiens - the only one on the entire globe - is able to rebel against the intentions of a selfish gene.

The translation is verified according to the anniversary English edition of 2006.

"Pseudoscience and paranormal activity. Critical view. Jonathan Smith.

Confidently operating on the data of psychology, physics, logical analysis, history, Jonathan Smith leads the reader through the mysterious territories of the unknown, not letting him get lost among complex scientific concepts and helping to distinguish between incredible truth and plausible deception.

The views on science of three great Russian writers – A.P. Chekhov, F.M. Dostoevsky and L.N. Tolstoy. The study of science in such a context yields unexpected and interesting results. Keywords: science, art, fiction.

Key word: science, art, fiction literature

The problem of the relationship between science and art has a long history and is solved from different or directly opposite positions. The idea was popular that scientific, discursive thinking crowds out the intuitive and transforms the emotional sphere. The phrase "Death of art" has become fashionable. The threat to art was directly associated with science and technology. A machine, unlike a person, has perfection and enormous productivity. She challenges artists. Therefore, art faces a choice: either it obeys the principles of machine technology and becomes mass, or it finds itself in isolation. The apostles of this idea were the French mathematician and esthetician Mol and the Canadian specialist in mass communications McLuhan. Mol argued that art was losing its privileged position, becoming a kind of practical activity, being adapted by scientific and technological progress. The artist turns into a programmer or communicator. And only if he masters the strict and universal language of the machine, can he retain the role of the discoverer. His role is changing: he no longer creates new works, but ideas about new forms of influence on the human sensory sphere. These ideas are realized by technology, which plays no less a role in art than in the creation of a lunar rover. In essence, this was only the first preventive war against the idea of the sacredness of artistic creativity and the very value of the author. Nowadays, the Internet has carried these ideas to the end and, as is usually the case, to a caricature.

But there is also a directly opposite concept of the relationship between science and aesthetic values. For example, the French aesthetician Dufresne believed that art in its traditional sense was indeed dying. But this does not mean that art in general is dying or should die under the aggressive pressure of science. If art is to survive, it must stand in opposition to the social and technical milieu, with their ossified structures hostile to man. Breaking with traditional practice, art does not ignore reality at all, but, on the contrary, penetrates into its deeper layers, where object and subject are already indistinguishable. In a sense, this is a variant of the German philosopher Schelling. Art thus saves man. But the price of such salvation is a complete rupture of art and science.

Of all the arts, science and fiction have the most tense relationship. This is explained, first of all, by the fact that both science and literature use the same way of expressing their content - a discursive way. And although there is a huge layer of symbolic specific language in science, the main one remains colloquial. One of well-known representatives Analytical philosophy Peter Strawson believed that science needs a natural language for its comprehension. Another analyst, Henry N. Goodman, believes that versions of the world consist of scientific theories, pictorial representations, literary opuses, and the like, it is only important that they meet the standard and tested categories. Language is a living reality, it does not recognize boundaries and flows from one subject field to others. That is why writers follow science so closely and jealously. How do they feel about her? To answer this question, it is necessary to examine the entire literature separately, because there is no single answer. It is different for different writers.

The foregoing applies primarily to Russian literature. It's clear. A poet in Russia is more than a poet. And literature has always performed with us more features than art should be. If, according to Kant, the only function of art is aesthetic, then in Russia literature both taught and educated, was part of politics and religion, and preached moral maxims. It is clear that she was following science with jealous interest - is that part of her plot not grabbing? Moreover, every year and century more and more objects fell into the sphere of interests of science, and its subject was steadily expanding.

Part 1. A.P. Chekhov.

“I passionately love astronomers, poets, metaphysicians, assistant professors, chemists and other priests of science, to whom you rank yourself through your smart facts and branches of sciences, i.e. products and fruits... I am terribly devoted to science. This nineteenth-century sail ruble has no value for me; science has obscured it before my eyes with its further wings. Every discovery torments me like a carnation in the back ....». Everyone knows these lines from Chekhov's story "Letter to a learned neighbor." “This cannot be, because this can never be,” etc. And even people, well those who know creativity Chekhov, they think that Chekhov's attitude to science ends with such jokes. And yet this is a profound delusion. None of the Russian writers took science as seriously and with such respect as Chekhov. What worried him in the first place? First of all, Chekhov thought a lot about the problem of the connection between science and truth.

The hero of the story "On the Way" says: "You don't know what science is. All sciences, how many there are in the world, have the same passport, without which they consider themselves unthinkable - the desire for truth. Each of them has as its goal not utility, not convenience in life, but truth. Amazing! When you begin to study any science, you are first of all struck by its beginning. I will tell you that there is nothing more fascinating and grandiose, nothing so stunning and captures the human spirit as the beginning of some kind of science. From the very first five or six lectures you are inspired by the brightest hopes, you already seem to yourself to be the owner of the truth. And I devoted myself to the sciences selflessly, passionately, like a beloved woman. I was their slave, and apart from them I did not want to know any other sun. Day and night, without straightening my back, I crammed, went bankrupt on books, wept when, before my eyes, people exploited science for their own purposes. But the trouble is that this value - the truth - is gradually beginning to erode.

And Chekhov continues bitterly: “But I didn’t get carried away for a long time. The thing is that every science has a beginning, but no end at all, just like a periodic fraction. Zoology has discovered 35,000 species of insects, chemistry has 60 simple bodies. If, in time, ten zeros are added to the right of these figures, zoology and chemistry will be just as far from their end as they are now, and all modern scientific work consists in incrementing numbers. I enlightened to this trick when I discovered the 35001st species and did not feel satisfied” [ibid.]. In the story "The Mummers", a young professor gives an introductory lecture. He assures that there is no greater happiness than to serve science. “Science is everything! he says. “She is life.” And they believe him. But he would have been called a mummer if they had heard what he said to his wife after the lecture. He told her: “Now I am, mother, a professor. A professor has ten times more practice than an ordinary doctor. Now I'm counting on 25 thousand a year.

It's just amazing. More than 60 years before the German philosopher Karl Jaspers, Chekhov tells us that truth disappears from the value horizon of science and the motives for doing science begin to become vulgar and philistine. Of course, he speaks in a specific way, as only Chekhov could say.

The next problem that concerns Chekhov is the problem of value-laden science. In the story “And the beautiful must have limits,” the collegiate registrar writes: “I also cannot keep silent about science. Science has many useful and wonderful qualities, but remember how much evil it brings if a person who indulges in it crosses the boundaries established by morality, the laws of nature, and so on? .

Chekhov was also tormented by the attitude of the inhabitants to science, and its social status. “People who have completed a course in special institutions sit idle or occupy positions that have nothing to do with their specialty, and thus higher technical education is still unproductive with us, ”Chekhov writes in the story“ The Wall ”.

In The Jumper, the writer unequivocally speaks of his sympathy for the exact sciences and the hero, the physician Dymov, and his wife, the jumper Olenka, realizes only after the death of her husband that she lived with an extraordinary person, a great man, although he did not understand operas and other arts. “Missed! Missed!” she cries.

In the story "The Thinker", the prison warden Yashkin talks with the warden of the county school:

“In my opinion, there are too many superfluous sciences.” “That is, how is it, sir,” Pifov asks quietly. - What sciences do you find superfluous? – “All sorts of… The more sciences a person knows, the more he dreams of himself… There is more pride… I would hang all these sciences. Well, well, I’m already offended. ”

Another truly visionary moment. In the story “Duel”, the zoologist von Koren says to the deacon: “The humanities that you are talking about will only satisfy human thought when, in their movement, they meet with exact sciences and go with them. Whether they will meet under a microscope, or in the monologues of a new Hamlet, or in a new religion, I do not know, but I think that the earth will be covered with an ice crust before this happens.

But even if you are not disillusioned with science, if truth, science and teaching are the whole meaning of your life, is that enough for happiness? And here I want to remind you of one of Chekhov's most poignant stories, A Boring Story. The story is really boring, almost nothing happens in it. But it is about us, and I cannot ignore it in promoting this story. The hero is an outstanding, world-famous scientist - a physician, professor, privy councilor and holder of almost all domestic and foreign orders. He is seriously and terminally ill, suffers from insomnia, suffers and knows that he has only a few months left to live, no more. But he cannot and does not want to give up his favorite business - science and teaching. His story about how he lectures is a real methodological guide for all teachers. His day starts early and at a quarter to ten he should start lecturing.

On the way to the university, he thinks over the lecture, and now he comes to the university. “And here are the gloomy, not repaired university gates for a long time, a bored janitor in a sheepskin coat, a broom, a pile of snow ... On a fresh boy who came from the provinces and imagines that the temple of science is indeed a temple, such gates cannot make a healthy impression. In general, the dilapidation of university buildings, the gloom of corridors, the soot of walls, the lack of light, the dull appearance of steps, hangers and benches in the history of Russian pessimism occupy one of the first places along with predisposing causes ... A student whose mood is mostly created by the situation, at every step, where he is learning, he must see only tall, strong, graceful in front of him ... God save him from skinny trees, broken windows, gray walls and doors upholstered with torn oilcloth.

His thoughts about his assistant, the dissector, who prepares preparations for him, are curious. He fanatically believes in the infallibility of science and, above all, of everything that the Germans write. “He is confident in himself, in his drugs, knows the purpose of life and is completely unfamiliar with doubts and disappointments, from which talents turn gray. A slavish worship of authority and no need to think for yourself." But here comes the lecture. “I know what I will read about, but I don’t know how I will read, where I will start and how I will end. In order to read well, that is, not boring and for the benefit of the listeners, in addition to talent, you also need to have skill and experience, you need to have the clearest idea of \u200b\u200bits own strengths, of those to whom you read, and of what constitutes the subject of your speech. In addition, you have to be a man of your own mind, watch vigilantly and not lose your field of vision for a second .... In front of me are one and a half hundred faces that do not look like one another ... My goal is to defeat this many-headed hydra. If every minute while I am reading I have a clear idea of the degree of her attention and the power of understanding, then she is in my power ... Further, I try to make my speech literary, the definitions are short and precise, the phrase is as simple and beautiful as possible. Every minute I must rein myself in and remember that I have only an hour and forty minutes at my disposal. In a word, a lot of work. At the same time, you have to pretend to be a scientist, and a teacher, and an orator, and it’s bad if the speaker defeats the teacher and scientist in you, or vice versa.

You read for a quarter of an hour, half an hour, and then you notice that the students begin to glance at the ceiling, one will climb for a scarf, the other will sit comfortably, the third will smile at his thoughts .... This means that attention is tired. We need to take action. Taking the first opportunity, I say some kind of pun. All one and a half hundred faces are smiling broadly, their eyes are gleaming merrily, the rumble of the sea is heard for a short while. I laugh too. Attention is refreshed and I can continue. No sports, no entertainments and games gave me such pleasure as lecturing. Only at lectures could I give myself over to passion and understand that inspiration is not an invention of poets, but actually exists.

But now the professor falls ill and, it would seem, we have to give up everything and take care of health, treatment. “My conscience and mind tell me that the best thing I could do now is give the boys a farewell lecture, tell them the last word, bless them and give up my place to a man who is younger and stronger than me. But let God judge me, I do not have the courage to act according to my conscience... As 20-30 years ago, so now, before my death, I am only interested in science. emitting last breath, I will still believe that science is the most important, most beautiful and necessary thing in human life, that it has been and will be the highest manifestation of love, and that only through it alone will man conquer nature and himself.

This faith may be naive and unjust in its foundation, but it is not my fault that I believe this way and not otherwise; I cannot overcome this faith in myself” [ibid.]. But if this is so, if science is the most beautiful thing in human life, then why do you feel like crying while reading this story? Probably because the hero is still unhappy. Unhappy because he is terminally ill, unhappy in his family, unhappy in his sinless love for his pupil Katya. And the last phrase "Farewell, my treasure", as well as the phrase "Where are you, Miss?" from another story by Chekhov - the best that is in world literature, from which the heart shrinks.

Extraordinarily interesting are Chekhov's reflections both as a doctor and as a writer on the problem of "genius and madness", which is still relevant today. One of the the best stories Chekhov "The Black Monk". The hero Kovrin is a scientist, a very talented philosopher. He is ill with manic-depressive psychosis, which Chekhov, as a doctor, describes with scrupulous accuracy. Kovrin comes for the summer to visit his friends, with whom he practically grew up and marries the owner's daughter Tanya. But soon the manic phase sets in, hallucinations begin, and a frightened Tanya and her father begin to fight for his treatment. This causes Kovrin nothing but irritation. “Why, why did you treat me? Bromic drugs, idleness, warm baths, supervision, cowardly fear at every sip, at every step - all this will eventually drive me to idiocy. I went crazy, I had delusions of grandeur, but on the other hand I was cheerful, cheerful and even happy, I was interesting and original.

Now I have become more reasonable and solid, but I am like everyone else: I am mediocrity, I am bored with life ... Oh, how cruelly you treated me. I saw hallucinations, but who cares? I ask: who bothered? “How happy Buddha and Mohammed or Shakespeare that good relatives and doctors did not cure them of ecstasy and inspiration. If Mohammed had taken potassium bromide from his nerves, worked only two hours a day and drank milk, then after this wonderful person there would be as little left as after his dog. Doctors and good relatives will eventually do what will make humanity dumb, mediocrity will be considered a genius and civilization will perish” [ibid.]. IN last letter She writes to Tanya to Kovrin: “Unbearable pain burns my soul ... Damn you. I took you for an extraordinary person, for a genius, I fell in love with you, but you turned out to be crazy. This is a tragic mismatch of inner self-perception brilliant man and the perception of him by those around him, whom he actually makes unhappy - a depressing circumstance that science has not yet coped with.

Part 2. F. M. Dostoevsky

We see a completely different image of science in the work of F.M. Dostoevsky. Probably the most important components of this image are in Possessed and The Brothers Karamazov. In Possessed, Dostoevsky speaks not of science in general, but more of social theories. "Demons" seem to capture the moments when a social utopia with whimsical fantasies and romance acquires the status of a "textbook of life" and then becomes a dogma, the theoretical foundation of a nightmarish turmoil. Such a theoretical system is being developed by one of the heroes of The Possessed, Shigalev, who is sure that there is only one way to earthly paradise - through unlimited despotism and mass terror. All to one denominator, complete equality, complete impersonality.

Dostoevsky's undisguised disgust for such theories that came from Europe, he transfers to the whole of European enlightenment. Science is the main driving force European enlightenment. “But in science, only that,” says the elder Zosima in The Brothers Karamazov, “is subject to feelings. The spiritual world, the higher half of the human being, is completely rejected, expelled with a certain triumph, even with hatred. After science, they want to get along without Christ.” Dostoevsky believes that Russia should receive from Europe only external applied side knowledge. “But we have nothing to draw on for spiritual enlightenment from Western European sources, for the full presence of Russian sources ... Our people have been enlightened for a long time. Everything that they desire in Europe has long been in Russia in the form of the truth of Christ, which is wholly preserved in Orthodoxy.” This did not prevent Dostoevsky from speaking sometimes of an extraordinary universal love for Europe.

But, as D. S. Merezhkovsky aptly notes, this extraordinary love is more like an extraordinary human hatred. “If you knew,” writes Dostoevsky in a letter to a friend from Dresden, “what a bloody disgust, to the point of hatred, Europe has aroused in me for itself in these four years. Lord, what prejudices we have about Europe! Let them be scientists, but they are terrible fools... The local people are literate, but unbelievably uneducated, stupid, stupid, with the basest interests” [ibid.]. How can Europe respond to such “love”? Nothing. Except hate. “In Europe, everyone is holding a stone in their bosom against us. Europe hates us, despises us. There, in Europe, they decided long ago to put an end to Russia. We cannot hide from their gnashing, and someday they will rush at us and eat us.”

As for science, it is, of course, the fruit of the intelligentsia. “But having shown this fruit to the people, we must wait what the whole nation will say, having accepted science from us.”

But for some reason it is still needed, science, since it exists? And just then N.F. Fedorov with his project of the general salvation of the ancestors.

The doctrine of the common cause was born in the autumn of 1851. For almost twenty-five years, Fedorov did not put it on paper. And all these years he dreamed that Dostoevsky would appreciate the project. Their difficult relationship a wonderful work by Anastasia Gacheva is dedicated to this.

A. Gacheva emphasizes that in many topics the writer and the philosopher, without knowing it, go in parallel. Their spiritual vectors move in the same direction, so that the holistic image of the world and man, which Fedorov builds, acquires volume and depth against the background of Dostoevsky's ideas, and many of Dostoevsky's intuitions and understandings respond and find their development in the works of the philosopher of the common cause. Dostoevsky's thought is moving towards the scientific and practical side of the project. “THEN WE SHALL NOT BE AFRAID OF SCIENCE. WE WILL SHOW EVEN NEW WAYS IN IT” - in capital letters Dostoevsky denotes the idea of a renewed, Christian science. It appears in the outlines of Zosima's teachings, echoing other statements that outline the theme of transfiguration: “Your flesh will change. (Light of Tabor). Life is paradise, we have the keys.

However, in the final text of the novel, there is only the image of a positivist-oriented science that does not care about any higher causes and, accordingly, leads the world away from Christ (Mitya Karamazov's monologue about "tails" - nerve endings: it is only thanks to them that a person both contemplates and thinks, and not because that he is “some kind of image and likeness there.” In the late 1890s and early 1900s, Fedorov began to hear themes on a new turn, which at one time united him with Dostoevsky back in the 1870s. The secular civilization of modern times, which deified the vanity of vanities, serving the god of consumption and comfort, points to the symptoms of an anthropological crisis that were clearly identified by the end of the 19th century - it was this crisis that Dostoevsky represented in his underground heroes, pointing to the dead end of godless anthropocentrism, the absolutization of man as he is.

Curious in this regard is the attempt of modern researchers of Dostoevsky's work to present the attitude of the writer to the new, in particular, nuclear science. I. Volgin, L. Saraskina, G. Pomerants, Yu Karyakin reflect on this.

As G. Pomerants noted, Dostoevsky in the novel "Crime and Punishment" created a parable about the deep negative consequences of "naked" rationalism. “The point is not in a separate false idea, not in Raskolnikov's mistake, but in the limitations of any ideology. “It’s also good that you only killed the old woman,” said Porfiry Petrovich. “And if you came up with another theory, then, perhaps, you would have done a hundred million times more ugly thing.” Porfiry Petrovich was right. The experience of recent centuries has shown how dangerous it is to trust logic without believing it with the heart and spiritual experience. The mind that has become a practical force is dangerous. The scientific mind is dangerous with its discoveries and inventions. The political mind is dangerous with its reforms. We need systems of protection from the destructive forces of the mind, as at a nuclear power plant - from an atomic explosion.

Yu. Karyakin writes: “There are great discoveries in science… But there are also great discoveries of absolutely suicidal and (or) self-saving… spiritual-nuclear energy of a person in art - INCOMPARALLIBLY “more fundamental” than all… scientific discoveries. Why… Einstein, Mahler, Bekhterev… treated Dostoevsky in almost exactly the same way? Yes, because in a person, in his soul, everything converges, absolutely all lines, waves, influences of all the laws of the world ... all other cosmic, physical, chemical and other forces. It took billions of years for all these forces to concentrate at this one point only…”.

I. Volgin notes: “Of course, ... you can ... resist world evil exclusively with the help of aircraft carriers, nuclear bombs, tanks, special services. But if we want to understand what is happening to us, if we want to treat not the patient, but the disease, we cannot do without the participation of those who have taken on the mission of “finding a person in a person” .

In a word, we, who are in a state of the deepest global crises and in connection with the nuclear threat, are obliged, according to many philosophers and scientists, to go through dangerous revelations about man and society, through the most complete knowledge of them. This means that it is impossible to ignore Dostoevsky and the study of his work.

Part 3. L. N. Tolstoy

In January 1894, the 9th All-Russian Congress of Naturalists and Doctors took place, at which actual problems molecular biology. L. N. Tolstoy was also present at the congress, who spoke about the congress as follows: “Scientists have discovered cells, and there are some little things in them, but they themselves don’t know why”

These "things" do not give him rest. In the Kreutzer Sonata, the hero says “science has found some kind of leukocytes that run in the blood and all sorts of unnecessary nonsense,” but he couldn’t understand the main thing. Tolstoy considered all doctors to be charlatans. I.I. Mechnikov, laureate Nobel Prize called a fool. N.F. Fedorov, who had never raised his voice against anyone in his life, could not stand it. He tremblingly showed Tolstoy the treasures of the Rumyantsev Library. Tolstoy said: “How many people write nonsense. All this should have been burned." And then Fedorov shouted: "I have seen many fools in my life, but this is the first time such as you."

It is infinitely difficult to talk about the attitude of L.N. Tolstoy to science. What is this? Disease? Obscurantism reaching obscurantism? And it would be possible not to talk about it, to keep silent, as for many years admirers and researchers of I. Newton's work hushed up his pranks with alchemy. But after all, Tolstoy is not just a brilliant writer, probably the first in a series of Russian and world literature. For Russia, he is also a prophet, an almost non-canonized saint, a seer, a teacher. Walkers go to him, thousands of people write to him, they believe him like God, they ask for advice. Here is one of the letters - a letter from the Simbirsk peasant F.A. Abramov, which the writer received at the end of June 1909.

F. A. Abramov turned to L. N. Tolstoy with a request to clarify the following questions: “1) How do you look at science? 2) What is science? 3) Visible shortcomings of our science. 4) What has science given us? 5) What should be required of science? 6) What transformation of science is needed? 7) How should scientists relate to the dark mass and physical labor? 8) How to teach children younger age? 9) What is needed for youth? . And Tolstoy answers. This is a very voluminous letter, so I will pay attention only to the main points. First of all, Tolstoy defines science. Science, he writes, as it has always been understood and is understood now by the majority of people, is the knowledge of the most necessary and most important objects of knowledge for human life.

Such knowledge, as it cannot be otherwise, has always been, and is now only one thing: the knowledge of what every person needs to do in order to live in this world as best as possible that short period of life that is determined for him by God, fate. , the laws of nature - as you wish. In order to know this how the best way to live your life in this world, you must first of all know that it is definitely good always and everywhere and for all people, and that it is definitely bad always and everywhere and for all people, i.e. know what to do and what not to do. In this, and only in this, there has always been and continues to be true, real science. This question is common to all mankind, and we find the answer to it in Krishna and Buddha, Confucius, Socrates, Christos, Mahomet. All science comes down to loving God and neighbor, as Christ said. To love God, i.e. to love above all the perfection of good, and to love your neighbor, i.e. love every person as you love yourself.

So true, real science, needed by all people, is short, simple, and understandable, says Tolstoy. What the so-called scientists consider to be science, by definition, is no longer science. People who are now engaged in science and are considered scientists study everything in the world. They all need the same. “They, with equal diligence and importance, investigate the question of how much the Sun weighs and whether it will converge with such or such a star, and which goats live where and how they are bred, and what can be done from them, and how the Earth became the Earth, and how grass began to grow on it, and what kind of animals, and birds, and fish are on Earth, and which ones were before, and which king fought with which one and to whom he was married, and who, when, composed poems and songs and fairy tales, and what laws are needed, and why prisons and gallows are needed, and how and with what to replace them, and from what composition what stones and what metals, and how and what vapors are and how they cool, and why one Christian church religion is true, and how to make electric motors and airplanes, and submarines, etc., etc., etc.

And all these are sciences with the strangest pretentious names, and all this ... there is no and cannot be an end to research, because there is a beginning and an end to business, but there can be no end to trifles. And these trifles are dealt with by people who do not feed themselves, but who are fed by others and who, out of boredom, have nothing more to do than engage in any kind of fun. Further, Tolstoy distributes the sciences into three departments according to their goals. The first department is the natural sciences: biology in all its divisions, then astronomy, mathematics and theoretical, i.e. unapplied physics, chemistry and others with all their subdivisions. The second department will be made up of applied sciences: applied physics, chemistry, mechanics, technology, agronomy, medicine and others, aimed at mastering the forces of nature to facilitate human labor. The third department consists of all those numerous sciences, the purpose of which is to justify and affirm the existing social order. Such are all the so-called theological, philosophical, historical, legal, political sciences.

The sciences of the first department: astronomy, mathematics, in particular "so beloved and praised by the so-called educated people biology and the theory of the origin of organisms” and many other sciences that aim only at curiosity cannot be recognized as sciences in the exact sense of this, because they do not meet the basic requirement of science – to tell people what they should and should not do in order to their life was good. Having dealt with the first section, Tolstoy takes on the second. Here it turns out that the applied sciences, instead of making life easier for a person, only increase the power of the rich over the enslaved workers and increase the horrors and atrocities of wars.

There remains the third category of knowledge, called science, knowledge aimed at justifying the existing structure of life. This knowledge not only does not meet the main condition of what constitutes the essence of science, serving the welfare of people, but pursues a directly opposite, quite definite goal - to keep the majority of people in the slavery of a minority, using for this all kinds of sophisms, false interpretations, deceptions, frauds ... I think that it is superfluous to say that all this knowledge, aimed at evil, and not the good of mankind, cannot be called science, Tolstoy emphasizes. It is clear that for these numerous trifling activities, the so-called. scientists need helpers. They are recruited from the people.

And here the following happens to young people going into science. Firstly, they break away from the necessary and useful work, and secondly, filling their heads with unnecessary knowledge, they lose respect for the most important moral teaching about life. And those in power know this, and therefore, without ceasing, by all possible means, lures, bribes, they lure people from the people to the study of false science and scare them away from the real, true science with all kinds of prohibitions and violence,” Tolstoy emphasizes. Do not succumb to deception, calls Lev Nikolaevich. “And this means that parents should not send their children, as they do now, to schools organized by the upper classes to corrupt them, and adult boys and girls, breaking away from honest work necessary for life, should not strive and not enter educational institutions arranged to corrupt them. .

Just stop people from the people from enrolling in government schools, and the false science, which is not needed by anyone except one class of people, will not only be destroyed by itself, but the science that is always necessary and inherent in human nature, the science of how to best before one's conscience, before God, to live a certain period of life for everyone. This letter... And in the novels Tolstoy colors his attitude to science and education with artistic means.

It is known that Constantine Levin is the alter ego of Tolstoy. Through this hero, he expressed the most reverent questions for him - life, death, honor, family, love, etc.

Levin's brother Sergei Koznyshev, a scientist, discusses a fashionable topic with a well-known professor: is there a border between mental and physiological processes in human activity and where is it? Levin gets bored. He came across the articles in the journals that were discussed and read them, being interested in them as the development of the foundations of natural science familiar to him as a naturalist at the university, but he never brought these scientific conclusions about the origin of man as an animal, about reflexes, about biology and sociology closer to those questions about the meaning of life and death for oneself, which in Lately came to his mind more and more often.

Moreover, he did not consider it necessary to convey this knowledge to the people. In a dispute with his brother, Levin resolutely declares that a literate peasant is much worse. I don’t need schools either, but they are even harmful, he assures. And when they try to prove to Levin that education is good for the people, he says that he does not recognize this as a good thing.

Here is such a colorful, diverse, controversial image we find science in the works of our great writers. But with all the diversity of points of view and their controversy, one thing is indisputable - they all reflected primarily on the moral security of science and its responsibility to man. And this is now - main plot in the philosophy of science.

The problem of the relationship between literature and science is not a new problem. She stood up more than once before art theorists, and before philosophers who develop the theory of knowledge, and before writers. However, she had never stood so sharply before. The gigantic successes achieved by science in recent decades are now having an unprecedented impact on all aspects of human life, including literature. At the same time, the role of art in our society is immeasurably growing, its cognitive and educational functions are intensifying, and its possibilities in promoting scientific knowledge are expanding.

What is the influence of science on literature? What are the tasks of literature in connection with the increased role of science in the life of society? And what are the ways to solve these problems?

These and many other questions are now worrying our writers, critics and scientists. That is why the editors of the journal Voprosy Literature decided to dedicate a special selection to this topic.

The problem of "Literature and Science" is unusually multifaceted. The articles and notes published below touch upon various aspects of it. First of all, it arises as a "theme of science" in art, as a task of creating bright, interesting images of scientists. This is the subject of articles by D. Granin, V. Kaverin, A. Koptyaeva, I. Grekova, A. Sharov, reflecting on the ways of solving this problem, telling about their work on books about scientists. At the time of Balzac, scientists did not yet occupy any prominent place in the minds of society, and consequently, in literature. Now the situation has changed radically. The scientist is increasingly becoming the protagonist of works of art. And this is no coincidence.

“Communist society is built on the basis of science. Science is the main weapon of communism. I believe that the role of scientists will grow every year and the future belongs to them. All this makes me go here, to physicists conducting research at the very forefront of science,” Galina Nikolayeva, who worked in last years over a novel about physics.

D. Granin emphasizes that scientific creativity should become one of the most important themes of our literature, because here heroic characters, sharp, often tragic conflicts open up for the writer. To reveal the poetry of creative work, to show people who are purposeful, convinced, passionately seeking the truth - the task is as responsible as it is fascinating.

Naturally, writers are primarily concerned with issues directly related to creative practice. So, A. Sharov, for example, speaks in detail about one of the main difficulties that an artist inevitably encounters when writing about scientists: whether to depict “science itself” with all its complexities, or is it enough to give everyone an understandable “model” of that scientific problem around which the conflict unfolds? “... A writer who wants to portray a scientist and his work often finds himself in a dead end. modern science- is incomprehensible, and the model by its nature is conditional, approximate.

But is incomprehensibility really an insurmountable obstacle? the author asks and expresses interesting considerations about how, in his opinion, this contradiction should be resolved.

In a number of articles published below, a persistent thought shines through: the writer must know well what he is going to tell the reader, and science is no exception in this respect. I. Grekova writes about this. This is also stated in the article by A. Koptyaeva: “... in whatever genre the writer works, he must carefully, conscientiously study the foundations of science and the very problem that he describes. Not only in journalism, but also in the novel, the essence of the scientific problem in question should be revealed with all clarity. Only then is it able to interest the reader, to involve him in the struggle that unfolds in the book, to make him worry about the outcome of this struggle and, thus, for the fate of the characters.

However, the task of the writer is not limited to studying the basics of science and the problem that he is going to describe. It is no less, and perhaps even more important, for a novelist to understand the psychology of a scientist.

V. Kaverin, recalling the work on the Open Book, says: “While working on The Two Captains, I surrounded myself with books on aviation and the history of the Arctic. Now their place was taken by microbiological works, and they turned out to be much more complicated. First of all, it was necessary to learn how to read these works differently from the way scientists read them themselves. To restore the train of thought of a scientist, to read behind the dry, short lines of a scientific article what this person lived, to understand the history and meaning of the struggle against enemies (and sometimes friends), which is almost always present in scientific work - this is the task, without solving which there was nothing to take on such a topic. It is necessary to understand what the scientist throws out of brackets - the psychology of creativity.

Doctor of Physical and Mathematical Sciences A. Kitaygorodsky devotes a significant part of his article to the same problem. It is psychology scientific creativity often remains unknown in books about scientists, and even distorted. The physicist's reflections on why this happens, although containing a lot of subjectivity, I think, will be of considerable interest to writers working in this field.

The range of issues related to popular science and science fiction literature is covered in the article Polish writer Art. Lem, as well as in the speeches of our science fiction writers A. Dneprov, V. Saparin, A. and B. Strugatsky.

D. Danin's article is devoted to "interaction" natural sciences and art. The author gives examples of such interaction, talks about how art attracts scientists, traces the ways in which science influences art and vice versa, reflects on the “probable patterns” of such mutual influence.

The question of the relationship between scientific and artistic thinking, what unites scientific and artistic knowledge and what distinguishes them, about the prospects for their development is considered in the article by B. Runin.

There is a lot of controversy in the materials published below.

Yes, this is understandable: after all, the problem posed has hardly been developed theoretically. The articles by D. Danin and B. Runin are debatable in a number of their provisions. Some of the theses found in other speeches, as well as subjective assessments of the works of certain artists, may also raise objections.

One cannot agree, for example, with the Strugatskys when they assert that “only a “short leg” with science, with scientific outlook, with the philosophy of science, now allows us to push the boundaries of traditional literary plots, look into a new, hitherto unseen world of gigantic human capabilities, extraterrestrial tendencies, hopes and mistakes. So to speak, the “scientific writer” can do more in literature than the “ordinary” writer!”

The following thesis of their article is clearly one-sided: “Modern literature of the upper class is philosophical literature. Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Feuchtwanger, Thomas Mann - these are gigantic examples of how every writer should approach his work today.

In this case, the authors of the article forget that the successful development of literature implies a variety of styles, forms, trends. It is impossible to declare one of its forms (in this case, "philosophical" literature) to be the most correct, the most fruitful and categorically declare that nowadays every writer should work in the traditions of Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Feuchtwanger and Thomas Mann. Are the traditions of Chekhov or Turgenev, Balzac and Hemingway, for example, bad?

There is no need to enumerate all those provisions that may cause controversy. In the published materials there is not, and cannot be, a complete unity of opinion, because each of the authors shares, first of all, his own experience.

However, the main pathos of most of the speeches is very instructive and deserves unconditional support. Art and literature should not fence themselves off from science, but draw closer to it, propagandizing its achievements and setting new tasks before it.

An example for Soviet writers in this regard is M. Gorky, who was deeply interested in the problems of science, followed its development, and rejoiced at its successes. It is significant that the articles, speeches and letters of the remarkable Soviet writer devoted to science, made up a whole volume, which will soon be published by the Nauka publishing house. The reader will see for himself how wide was the range of scientific interests of Alexei Maksimovich, how much strength and energy he gave to the rapprochement of science - with life, art - with science. In art and science, the writer saw not “antagonists”, but allies capable of working together miracles of transforming the world, awakening in a person his best qualities and aspirations. “I know of no force more fruitful, more capable of cultivating social instincts in man, than the forces of art and science,” he said in a speech he called “Science and Democracy.”

Many of Gorky's thoughts about the connection between literature and science, about the tasks and possibilities of a writer striving to be at the level of contemporary scientific knowledge, have not become outdated to this day. They help to better understand the problems now facing writers and other artists.

Science is now moving at such a pace that it is simply impossible to keep track of all its achievements. Even scientists themselves are not able to cover all branches of their science: there is an increasing differentiation and, accordingly, a narrower specialization. And if this is so, some writers conclude, then there is nothing to strive for mastering scientific knowledge. M. Gorky, faced with such conclusions, answered: “You say:“ It is almost impossible for a writer to be an encyclopedist. If this is your strong conviction, stop writing, because this conviction says that you are not able or do not want to learn. From a writer, unfortunately, they do not require that he be an encyclopedist - but they must be required. The writer must know as much as possible, must stand at the height of contemporary scientific knowledge. In our country, this is especially necessary and is achieved by many.”

Science describes the phenomena and processes of the surrounding reality. It gives a person the opportunity to:

Observe and analyze processes and phenomena,

Find out at a qualitative level the mechanism of their flow,

Enter quantitative characteristics;

Predict the course of the process and its results

Art, which includes fiction, reflects the world in images - verbal, visual.

Both of these methods of reflection real world complement and enrich each other. This is due to the fact that a person is naturally inherent in the relatively independent functioning of two channels for the transmission and processing of information - verbal and emotional-figurative. This is due to the properties of our brain.

Science and art reflect social consciousness in different ways. The language of science - concepts, formulas. The language of art is images. Artistic images evoke in the minds of people persistent, vivid, emotionally colored ideas, which, supplementing the content of concepts, form a personal attitude to reality, to the material being studied. Formulas, relationships, dependencies can be beautiful, but you need to be able to feel it, then studying, instead of a harsh necessity, can become difficult, but pleasant business. In works of art, there are often pictures of physical phenomena in nature, descriptions of various technical processes, structures, materials, information about scientists. Science fiction reflects many scientific assumptions and hypotheses. A special vision of the world, mastery of the word and the ability to generalize allows writers to achieve surprisingly accurate, easily conceivable descriptions in their works.

The description of scientific knowledge is found in classical literature, as well as in modern times. Such descriptions are especially in demand in the genre of science fiction, since in its essence it is based on the presentation of various scientific hypotheses expressed in the language of fiction.

Fantasy as a technique, as a means of expression, belongs entirely to the form of a work of art, or rather, to its plot. But to understand the alignment and relationships social characters in their individual manifestation can only be based on the situation of the work, which is a category of content.

Science fiction, if considered in this regard, has the same subject as art - "the ideologically conscious characteristic of the social life of people and, in one way or another, the characteristic of the life of nature" with an emphasis mainly on the second part of this definition. Therefore, one cannot agree with the conclusions of T. A. Chernysheva, who believes that “the specifics ... (science fiction. - V. Ch.) is not that literature comes new hero- a scientist, and not in the fact that the social, “human” consequences of scientific discoveries become the content of science fiction works”, but in the fact that in “science fiction ... science fiction gradually stood out new topic: man and natural habitat, and art is now interested in the physical properties of this environment, and it is perceived not only in an aesthetic aspect.

It is possible that the artist as a person may be interested in certain aspects of physical phenomena. environment or nature in general. Examples of such interest, when a writer, a poet is not limited to purely artistic field activity, in the historical and literary process a lot. It suffices to recall in this connection the names of Goethe, Voltaire, Diderot, etc.

However, the question is not so much about justifying or condemning such an interest, but about the nature of this interest: either the “physical properties of the environment” are of interest to the writer, primarily in their essential moments, as a manifestation of certain objective laws of nature, or they are realized through the prism features of human life, thereby receiving a certain understanding and emotional and ideological assessment. In the first case, if the artist tries to create piece of art on the basis of a system of knowledge that has been consolidated in his theoretical thinking, it will inevitably be illustrative, without reaching that degree artistic generalization and expressiveness, which is inherent in works of art.

If, however, the "physical properties of the environment" acquire one or another emotional and ideological orientation due to the writer's ideological worldview, it can become the subject of art in general and science fiction in particular. The complexity of differentiating modern science fiction in its substantive significance lies in the fact that it is able to act as a reflection of the prospects for the development of science and technology, or " physical properties environment”, carrying out in a figurative form the popularization of certain problems or achievements of science and technology, and the “figurative form” in such a case does not go beyond illustrativeness. And at the same time, "science" fiction, which was born and completely took shape on turn of XIX- XX centuries, "interested" in the problems and themes of scientific achievements that bear the imprint of the social characteristics of the life of people and society in their national-historical conditionality. In this case, we can conditionally single out two “branches” in science fiction, in terms of its content: science fiction, which cognizes and reflects the problems of the natural sciences in their social and ideological orientation, and science fiction, which is “interested” in the problems of social sciences.

However, modern "science" fiction is not limited to the genre of utopia. The data of the social and natural sciences, in addition to their objective cognitive value, more and more influence the social relationships of people, expressed both in changing and revising moral and ethical norms, and in the need to foresee the results of scientific discoveries for the benefit or to the detriment of all mankind. The industrial and technical revolution, which began in the 20th century, confronts mankind with a number of social, ethical, philosophical, and not only technical problems. The changes taking place in this "changing" world and caused by the development of science are what science fiction is "dealing with", which since the time of Wells has been called social. The essence of this kind of "science" fiction was best expressed by the Strugatsky brothers. “Literature,” they write, “should try to explore typical societies, that is, practically consider the whole variety of connections between people, collectives and the second nature created by them. Modern world is so complex, there are so many connections and they are so tangled that literature can solve this problem by means of certain sociological generalizations, by constructing sociological models, necessarily simplified, but preserving the most characteristic tendencies and regularities. Of course, the most important trends of these models continue to be typical people, but acting in circumstances typified not along the line of concreteness, but along the line of trends. "An example of such fiction can be the works of the Strugatskys themselves ("It's hard to be a god", etc.), "Return from the Stars" by Stanislav Lem, etc.

A number of outdated opinions about science fiction, which boiled down mainly to the fact that its content should be a scientific hypothesis, the goal - a scientific forecast, and the purpose - the popularization and propaganda of scientific knowledge, has now been refuted not so much by the efforts of critics and literary critics, but by the literary practice itself. . Most writers on science fiction now agree that it is a special branch of fiction with a specific area of creative interests and peculiar methods of depicting reality. But still most of works devoted to science fiction, is characterized by insufficient development of the positive part of the program, in particular, such a fundamental issue as the role and significance of the "principle of science", the solution of which could clarify a number of controversial issues related to the nature of science fiction and its artistic possibilities. For the student of modern science fiction, it is imperative to clarify the nature of its connection with science, as well as the meaning and purpose of such a community.

The first and, perhaps, the most serious consequence of the "scientificization" of science fiction was its modernity. The emergence of science fiction in the second half of the XIX century. was to a certain extent predetermined by the enormous acceleration (compared with previous centuries) scientific and technological progress, the dissemination of scientific knowledge in society, the formation of a scientific, materialistic vision of the world. The scientific was accepted as a plausible justification for the fantastic then, the writer G. Gurevich notes, “when technology gained strength and miracles began to be done outside the fences of factories: steam chariots without horses, ships without sails sailing against the wind.”

However, science fiction is not just an ordinary sign of the times. The scientific principle adopted by science fiction prepared and armed it for the development of the most complex modern problems.

Most science fiction writers agree with the idea that the criterion of science is necessary for fiction. “... The problem of the compass, the problem of the criterion cannot be removed,” notes A. F. Britikov, for whom the criterion of science in science fiction is equivalent to the criterion of a person. Sun. Revici obviously reduces the criterion of being scientific to the wish of a science fiction writer to know the area he has chosen well and not to make elementary errors against science: “It is ridiculous when a person who claims to be a soothsayer makes elementary scientific errors.” True, the critic immediately stipulates that scientific awareness for a science fiction writer is not the main and not the only necessary quality, and even an elementary scientific miscalculation made by him may not be reflected in the artistic merits of the work. To this we must also add that not every science fiction writer, as we know, claims to be a soothsayer. The question of scientific criteria in V. Mikhailov's article "Science Fiction" is complicated. The author of the article either claims that the one and only “scientific” word mentioned by the science fiction writer makes his work science fiction (as, for example, the word “rocket”) and agrees with the scientific nature of the Wells time machine, then criticizes modern science fiction writers, who use in their works the idea of a photon rocket and flight at subluminal speeds, since "calculations" were published that testify to the technical impossibility of both. Z. I. Fainburg expands the boundaries of science for science fiction as widely as possible, arguing that “in situations and decisions of science fiction, assumptions are made, as a rule, on the basis of at least an ideally possible, that is, at least fundamentally not contradicting the materiality of the world.”

In modern science fiction, there are many gradations, degrees of science. Some modern science fiction writers go much further than Wells on the path of turning scientific justification into a kind of artistic technique, increasing credibility, or just a sign of the times. Becoming more and more formal, scientific justification becomes more and more conditional.